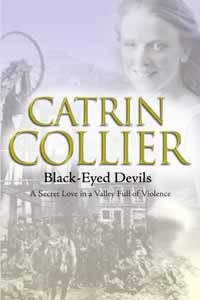

One look was enough. Amy Watkins and miner 'Big' Tom Kelly were in love. But can they keep their feelings secret or face the threat of death in a community torn apart by the miner's strike? Tonypandy, South Wales, 1911. Starving, striking miners fight soldiers and police on the picket lines for the right to earn a wage that will feed their families, while Irish labourers are brought in the take their place in the pits, for half their pay. Handsome 'Big' Tom Kelly, an Irish worker, comes to Wales looking for a better life and believes he has found it when he falls in love with Amy Watkins, the daughter of a strike leader. At night, the miners search out the Irish men, drag them from their beds, beat them and then hang them from the street lamp posts. Can Amy and Tom keep their love a secret forever? All they want is a future together. But in a world full of hatred, anger and violence, their dream seems impossible. Until another strike leader offers them a way out.

‘Straight down to the picket line at the Glamorgan colliery and straight back, Amy. No stopping to talk to anyone.’ Mary Watkins warned her daughter.

Amy’s blue eyes glittered with mischief. ‘It would be rude to ignore the neighbours if they talked to me, wouldn’t it, Mam?’

Mary tried not to smile. ‘Don’t look at me as if you don’t know what I’m talking about, my girl. Stay away from the soldiers and police.’

Amy wrinkled her nose. ‘You don’t have to tell me that. Father Kelly says the way the government is bringing them in, there’ll soon be more officers in Tonypandy than colliers. And, all the police do is watch the picket lines. You’d think they have better things to do. Like catch thieves.’

‘The only places worth thieving from these days are the pawn shops. There are more goods behind their counters than in our houses.’ Mary poured cold tea from the teapot, through a strainer into an enamel jug. ‘Fill the men’s cans for me, love. I’ll prepare the tea leaves for drying so they can go in the oven when we light the fire tonight. It’ll be their third “brew”, but it’s all the tea we’ll have until the next strike pay.’

Amy lifted down her father and brothers’ “snap” cans from the dresser. She filled them with cold tea and screwed on the tops. ‘Do you want me to take them anything besides this?’

‘Like what? The hens haven’t laid today and the cupboards are empty.’ Mary tried not to sound bitter but she couldn’t hide her feelings. It was a woman’s job to keep her family clean, warm and fed. She hated not being able to put enough food in front of her husband and grown sons when they returned from their “shifts” on the picket. And, no matter how much she and Amy cut back on their share, there was never enough for the six year old twins. Sam and Luke’s eyes had grown large in their thin faces, and they hadn’t had the energy to go out to play after school for months.

As a union man’s wife, Mary, had been one of the first women in the town to agree the strike was necessary. The miners had no choice but to withdraw their labour after management refused their request for a decent wage. But watching her children go hungry was almost more than she could bear.

Amy smiled. ‘The cupboards aren’t empty.’

‘What have you been up to?’ Mary was worried. Her eldest son, Jack, worked in the illegal drift mines the men had opened up on the mountain. Without the miners’ free ration of coal there was no fuel to heat water, houses or cook what little food they had. The men in the family insisted the coal that came out of the drifts was essential and worth the risk. But if Jack was caught, he would be fined. And a fine meant prison as they had no money.

Amy opened the cupboard and lifted out a cake tin. She opened it and showed her mother the contents. ‘There are twelve here.’

‘Welsh cakes? Wherever did you get them?’

‘I helped make them in the soup kitchen this morning after I cleaned the vegetables. Mrs Evans persuaded Mr Hopkin Morgan the baker to donate the ingredients but he didn’t give her any dried fruit.’

‘Not surprising the price, of it. It was good of him to give her the flour, sugar and margarine.’

‘We mixed the donated eggs with milk and water. Mostly water, but Father Kelly’s housekeeper gave us the last of her home made jam to fill them. Mrs Evans insisted I take these for helping.’

‘Leave them here,’ Mary said. ‘You know what your father is like. He won’t eat them in front of the other men and twelve cakes won’t give them a bite each. We’ll have one each tonight and keep the last four for the twins’ breakfast tomorrow.’

Amy returned the tin to the cupboard and packed the cans of cold tea into her basket.

‘Straight down and back,’ her mother reminded. ‘And, when you go to the soup kitchen this afternoon, take the jug and the last shilling from the strike pay and get it filled. There’s no bread left so it will be just soup tonight.’ Mary drained the teapot into a bowl and tipped the tea leaves on to a sheet of newspaper she’d spread on a baking tray.

‘Do you want me to get anything else while I’m in town, Mam?’ Amy picked up the cloak she shared with her mother. As hers was almost new, it had been one of the first things to be pawned when the men had come out on strike.

‘I’ll have ten of everything they’re giving away free.’ The joke was used by every miner’s wife in the Rhondda. Amy didn’t find it funny.

‘Won’t be long.’ Amy kissed her mother, walked down the passage opened the front door and left the house. Although it was late September, the winter rains had come early. Most of the women in the street were outside, scrubbing their front steps with stones and cold water because they couldn’t afford soap. Outdoors was wetter but no colder than their unheated stone houses.

‘You going down the picket line, love?’ Anna Jenkins who lived opposite the Watkins’s asked Amy.

‘Yes, Auntie Anna. I was about to call in and ask if you’d like me to take Uncle Gwilym’s tea down for him.’

‘If you don’t mind, love. I’ve got his can ready and it will save me a walk. I promised to go to the soup kitchen early to organize things for Father Kelly. He called in to tell me that he has to go out on parish business. Come in.’

Amy followed Anna into her house and up the stone flagged passage to the kitchen. It was as clean, bare and cold as her mother’s.

Anna handed her the can. ‘Tell him I’m sorry I have nothing more to give him.’

‘I will.’ Amy dropped it into her basket with the others.

‘And mind how you go.’

Amy had known Anna all her life. She was her mother’s closest friend and had moved to Tonypandy from Pontypridd the same time as her parents. ‘Mam’s given me the full lecture. No talking to soldiers or policemen.’

‘Or blacklegs.’

‘I won’t be seeing any. They hide behind the police line inside the colliery.’

Anna lowered her voice as she followed Amy to the door. ‘My Gwilym’s heard different. Management’s been bringing them into the town for the last two weeks and hiding them among the soldiers in the lodging houses. It’s best you avoid all strange men, Amy.’

‘I will. ‘Bye, Auntie Anna.’

Anna watched Amy until she turned the corner. Despite the rain and short rations there was a spring in Amy’s step. She suddenly remembered what it felt like to be young. Not that she had ever been as pretty as Amy. Tall, slender with silver blonde hair and deep blue eyes, Amy had attracted admiring looks from men since her fifteenth birthday. When she’d caught her husband, Gwilym, watching Amy, he’d said, “Anna, I might be nearer fifty than forty years old, but I can still recognise beauty when I see it. And Amy has something of the same look about her that you had when I married you fifteen years ago.”

Anna had been upset by the comparison. But she had been careful not to shed her tears in front of Gwilym.